The Rise and Fall of the Cover Image

In 1989, one of my prized possessions was a commemorative edition of Sports Illustrated, celebrating the 35th anniversary of the magazine's existence (and only in hindsight do I realize that this was a cynical cash ploy, that 35 is not a milestone that is typically celebrated--but when you have only lived 11 years, any anniversary that ends in zero or five really does seem significant). Anyway, this special edition contained an image of every cover of every SI ever published. I drooled over this thing like some pre-adolescents drool over Playboy. And though I lost track of it somewhere over the years and haven't seen it in a long time, a Google search confirms that I have a word-for-word recollection of a subhead on the title: "The Champ Ali Graces Our Cover for a Record 31st time." And the cover showed a then-contemporary picture of Muhammed Ali holding up a classic SI with himself on the cover.

Forget the cover jinx inanity--back then people talked about SI cover appearances as if it were a cultural currency. This special edition also had a table in back with the stats, so one could see in the pre-Wikipedia era which athletes had made the most cover appearances. (I noticed at the time that Jordan was gaining on Ali, and now he is far and away the leader all-time, with Tiger Woods also having passed The Greatest).

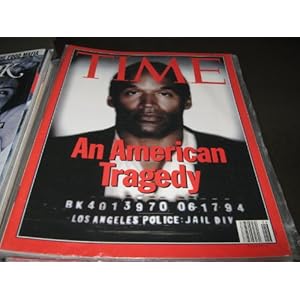

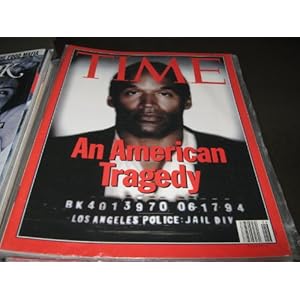

And I still remember when it was a big deal in 1992 when Bonnie Blair, Kristi Yamaguchi, and Kathy Ireland made the cover in successive weeks, marking the first time ever that women were featured on the cover three weeks in a row (though I think the fact that one of the above was a swimsuit model negates any claims that SI would have to progressivism). And this might have been the last time that I really thought about SI covers. But a couple years after that, in 1994, my attention turned to Time Magazine, accused of doctoring O.J. Simpson's mugshot to make him look worse.

It didn't help that Newsweek ran the same mugshot undoctored.

What all of these reminisces have in common is that they are from an era when weekly magazines shaped the way that we thought about the world around us. There was a daily media, but the place to go for thoughtful analysis and commentary, to take a step back from immediate events and try to put occurrences into context, was either the Sunday morning news shows or the glossy weekly magazines. But the latter offered something that the electronic media didn't have. Since TV was (and is) so ephemeral, even though it was a visual media, it was difficult for any television image to penetrate the national consciousness (interestingly, due to their repetitive nature, TV commercials were somewhat successful in this regard, especially the iconic political ads such as LBJ's little girl picking daisies and Dukakis in a tank). So it was cover images of magazines that often set the agenda for national conversations, that gave a concrete visual representation of abstract phenomena.

But ironically, because we are now in an era when media has made such representations exceedingly easy, they now proliferate and therefore lose their currency. The only way that a Newsweek cover can get traction anymore is if it is controversial on editorial grounds.

And that of course brings us to the Michelle Bachmann cover controversy. What intrigues me about this development is how many people probably first encountered this cover virtually. I wish there were stats on this; my guess would be that the majority of people who have seen this image have not seen the actual magazine itself. And this is ironic because the story has become viral on the basis that the cover depiction is supposedly important, that the decision that Newsweek editors make has some bearing on public perception of Michelle Bachmann. But, in another twist of irony, a Google search on "Newsweek" and "Bachmann" fails to locate the actual Newsweek story anywhere in the first five pages of results (I gave up looking after that).

It used to be that a handful of privileged editors would elevate certain images to the fore of public consumption. But we are fast approaching a world where no image will be automatically awarded a favored status. It will be up to the hive mind to determine what if any images will be seared into the minds of the masses...for better or for worse.

Tweet

Forget the cover jinx inanity--back then people talked about SI cover appearances as if it were a cultural currency. This special edition also had a table in back with the stats, so one could see in the pre-Wikipedia era which athletes had made the most cover appearances. (I noticed at the time that Jordan was gaining on Ali, and now he is far and away the leader all-time, with Tiger Woods also having passed The Greatest).

And I still remember when it was a big deal in 1992 when Bonnie Blair, Kristi Yamaguchi, and Kathy Ireland made the cover in successive weeks, marking the first time ever that women were featured on the cover three weeks in a row (though I think the fact that one of the above was a swimsuit model negates any claims that SI would have to progressivism). And this might have been the last time that I really thought about SI covers. But a couple years after that, in 1994, my attention turned to Time Magazine, accused of doctoring O.J. Simpson's mugshot to make him look worse.

It didn't help that Newsweek ran the same mugshot undoctored.

What all of these reminisces have in common is that they are from an era when weekly magazines shaped the way that we thought about the world around us. There was a daily media, but the place to go for thoughtful analysis and commentary, to take a step back from immediate events and try to put occurrences into context, was either the Sunday morning news shows or the glossy weekly magazines. But the latter offered something that the electronic media didn't have. Since TV was (and is) so ephemeral, even though it was a visual media, it was difficult for any television image to penetrate the national consciousness (interestingly, due to their repetitive nature, TV commercials were somewhat successful in this regard, especially the iconic political ads such as LBJ's little girl picking daisies and Dukakis in a tank). So it was cover images of magazines that often set the agenda for national conversations, that gave a concrete visual representation of abstract phenomena.

But ironically, because we are now in an era when media has made such representations exceedingly easy, they now proliferate and therefore lose their currency. The only way that a Newsweek cover can get traction anymore is if it is controversial on editorial grounds.

And that of course brings us to the Michelle Bachmann cover controversy. What intrigues me about this development is how many people probably first encountered this cover virtually. I wish there were stats on this; my guess would be that the majority of people who have seen this image have not seen the actual magazine itself. And this is ironic because the story has become viral on the basis that the cover depiction is supposedly important, that the decision that Newsweek editors make has some bearing on public perception of Michelle Bachmann. But, in another twist of irony, a Google search on "Newsweek" and "Bachmann" fails to locate the actual Newsweek story anywhere in the first five pages of results (I gave up looking after that).

It used to be that a handful of privileged editors would elevate certain images to the fore of public consumption. But we are fast approaching a world where no image will be automatically awarded a favored status. It will be up to the hive mind to determine what if any images will be seared into the minds of the masses...for better or for worse.

Tweet

1 Comments:

The democratization of images

Post a Comment

<< Home