"There was still a sense in 1986...writers around the world were in many ways at the center of the national argument, in a way we may feel is no longer the case....I don't know quite why it doesn't happen so much in America anymore. There was a time when writers like...Mailer and Sontag and Didion and DeLillo and Robert Stone...a whole generation of writers who very consciously looked for a public voice...I'm not sure who their equivalents today might be..."

--- Salman Rushdie at the 2011 PEN world voice festival.

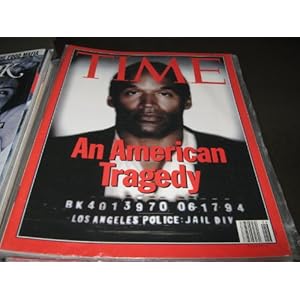

I've thought much about what Rushdie is saying above, even well before I heard him say it. I've long had the suspicion that my generation is the first in centuries that has had no desire for literary spokespeople. Rushdie of course will be forever remembered more for

fallout after writing

The Satanic Verses than for anything else. Twenty-five years later, it is still not a stretch of the imagination to assume that an extremist Muslim leader would call for the assassination of someone for blasphemy against Islam. But I don't think it is as easy to imagine a scenario where a novelist would be targeted. Perhaps in a telling indication about a change in society, it was

cartoonists who suffered in a more recent controversy.

So what exactly has changed to bring about a world where writers are less likely to face a fatwa, but also less likely to contribute to "national argument"? It's easy enough to blame technology, to assume that novelists have simply been superseded by tweeters. But I think there are a number of factors at work in diminishing the voice (and power) of the writer.

1) There was a time in the mid-20th Century that writers became rock stars. Kerouac and the beats, Wolfe, Kesey, Hunter S. Thompson and the like were lauded along with The Beatles and The Stones. Bob Dylan hung out with Alan Ginsburg. Rushdie himself made one of his rare public appearances during the fatwa at a U2 concert. So why aren't writers rock stars anymore? Perhaps because we don't really have rock stars anymore. I

wrote three years ago that we have entered an "archival era," that creative innovation has largely ceased and now we are just unpacking all that is out there, rehashing when appropriate. So if the writers of the past actually still speak, what need is there for new ones?

2) A significant way in which 20th Century writers achieved prominence was through the academy. Literary scholars appointed a Faulkner or a Joyce to a position of artistic merit, and subsequent generations were trained to esteem them as well. But eventually, scholars turned to deconstructing the canon rather than building it. When Roland Barthes wrote an

essay in 1967 called "Death of the Author" and Michel Foucault wrote "What is the Author?" two years later, the concept of a literary

sui generis was cast into disrepute. Should it be any surprise that when kids in college learn that it doesn't matter who wrote a book, that they quit looking for insight from people who write books?

3) It's a cliche that "It's easier to tear down than to build up." But in the past, that hasn't necessarily been true. It wasn't always easy to acquire a platform from which to tear down.

Robert Greene was a 16th Century English writer who would be completely forgotten today, if not for a pamphlet he wrote with a passage that appears to contain a jab at Shakespeare. This is noteworthy because there are few surviving documents from Shakespeare's contemporaries that reference The Bard, much less one that says something negative. But the document wouldn't have survived had Greene not had some degree of success himself as a writer, however modest relative to his immortal target. More recently, before Roland Barthes was a full-on poststructuralist committed to deconstructing authors, he was known as a master of semiotics, known and read by critics and scholars.

But now, thanks to the Internet, anyone can lob a stone and get a reaction. A couple of my favorite contemporary authors are Malcolm Gladwell and Chuck Klosterman. Both of them had surprising best sellers right before the explosion of the Web. They've written subsequent books in the "Web era," and while they have carved out highly successful careers and huge followings, they've got their

fair share of detractors, who flourish on the Web. Recently Klosterman and Gladwell allied themselves with Bill Simmons' new website Grantland, which led to a particularly scathing

critique from an anonymous blogger achieving some degree of notoriety.

I'm well aware of the danger of the implications (to say nothing of the hypocrisy) of asserting that only accomplished writers should be able to criticize accomplished writers. But at a certain point, when there is a culture of negativity, when it is infinitely easier to tear down somebody else's creation rather than to fashion one's own, we shouldn't be surprised when there is less supply or demand of writers that matter.

4) "One of the things I remember [about the 1986 PEN festival with Updike, Bellow, Sontag, etc]...which is really different than the PEN festivals we're having now is how bad-tempered it was, how all the writers were fighting with each other like cats and dogs"-- Rushdie

While conventional wisdom is that technology has caused a decline in overall civility in society, writers themselves are apparently getting along with each other better than they used to. But I'm not convinced this is something to be happy about. Writers have always tended toward the political left, but I get the sense that there used to be less of a codified dogmatism than there now exists. Christopher Hitchins strikes me as someone who is exceptional in his range of opinions--fervently anti-religious to the point of participating in organized debates with evangelicals, strongly in support of American interventionist policies in the Middle East including the Iraq invasion, and morally outraged about "enhanced interrogation techniques" to the point where he underwent waterboarding to bolster his claim that it is torture. But off the top of my head I can't come up with any more names of writers who have the ability to surprise with their opinions. Sure, a talented writer can still find a way to take a commonly-held idea and package and disseminate it in a compelling way. But once the content itself loses the edge of unpredictability and when style is the only thing that separates one writer from another, audiences will be less motivated to seek anyone out.

So whereas Shelley famously called writers "unacknowledged legislators of the word," maybe it is time to cut the last four words off of that quote.